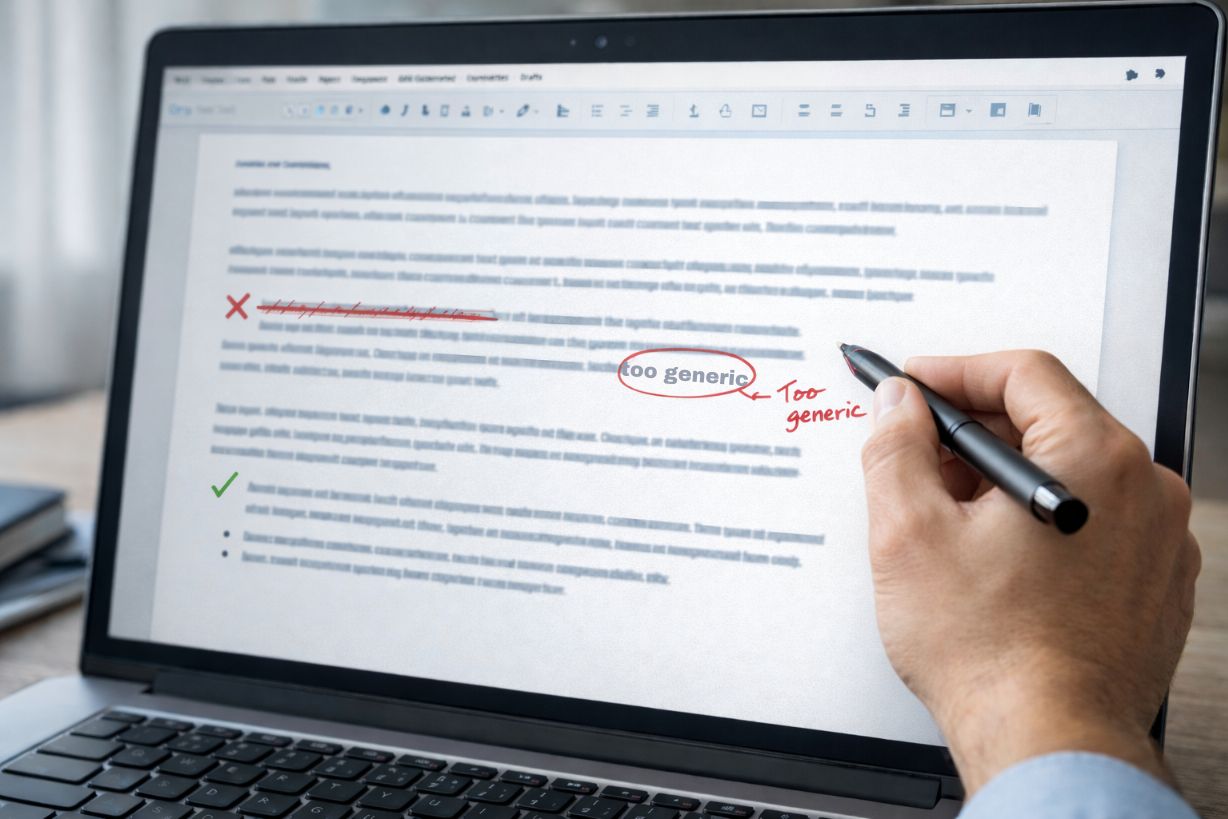

A human applying judgment to AI-generated content — deciding what to remove, refine, and keep before publication. Image Source: ChatGPT-5.2

Why AI Writing Sounds the Same — and Why Humans Are Responsible (Part 1)

Editor’s Note: This article is Part 1 of a two-part AiNews explainer examining why AI writing often appears repetitive — and why that perception misunderstands how AI systems actually work.

As artificial intelligence becomes more widely used in content creation, a familiar complaint has emerged: AI writing all sounds the same.

The critique is not entirely unfounded. Readers increasingly encounter articles, social posts, and newsletters that feel interchangeable — similar structures, similar phrasing, similar conclusions. But the underlying cause is often misunderstood.

The sameness many people attribute to AI is less about the technology itself, and more about how humans are using it.

Key Takeaways: Why AI Writing Sounds the Same

AI writing sounds repetitive not because AI lacks creativity, but because humans reuse the same prompts, templates, and incentives.

Large language models reflect the structure and intent of their inputs — narrow instructions produce narrow outputs.

Prompt culture and copy-paste incentives reward speed and engagement over clarity and original thinking.

AI operates on instructions, not intent, which makes human judgment critical before content is published.

Editorial judgment — deciding what matters, what to remove, and what to leave unsaid — is becoming a competitive advantage.

Confident-sounding AI output is not the same as sound judgment, especially when writers lack deep understanding of the topic.

AI does not eliminate the need for thinking — it raises the cost of skipping it.

The Real Source of Repetition in AI Content

Large language models are designed to recognize and reproduce patterns in language. This is not a weakness — it is what allows them to summarize information, adapt tone, and generate readable text quickly.

Repetition begins to emerge when those patterns are reinforced by how humans use the tools.

In practice, this means:

The same prompts get reused across industries, such as:

“Write a LinkedIn post about AI trends with a strong hook and three takeaways”

“Summarize this article in a conversational tone for executives”

“Rewrite this content to sound more thought-leadership focused”

“Optimize for clarity, brevity, and engagement”

The same article and post templates circulate on social media, often framed as formulas for success:

“I did X to get Y — copy my prompt”

Followed by dozens of lines of prompts meant to be reused verbatim

The same “best-performing” prompts are copied word-for-word, rather than adapted or reconsidered for a new audience or purpose

When thousands of people ask an AI system to write something like:

“A LinkedIn post about AI trends in 2025 using an engaging hook and three bullet points”

the results are naturally going to look and sound similar. The model is not failing — it is responding accurately to a narrowly defined request. When given narrow, repetitive inputs, it produces narrow, repetitive outputs.

What readers are reacting to is not a lack of ideas, but a lack of variation in instruction. When prompts prioritize speed, familiarity, and performance over perspective, the output reflects those priorities.

The “sameness” many people experience is not a sign that AI cannot generate original thinking. It is a sign that originality was never clearly asked for in the first place.

Prompt Culture and the Copy-Paste Incentive

As generative AI tools have gone mainstream, a parallel economy has emerged around prompts themselves. Prompt libraries, viral templates, and so-called “guaranteed engagement” formulas now circulate widely across social platforms and creator communities.

These resources are often presented as shortcuts — a way to unlock better AI output quickly, especially for people who are new to writing or publishing. They lower the barrier to entry and reduce friction in getting content out the door.

But they also reflect the realities of modern marketing incentives.

Many companies still prioritize reach above all else. Teams are measured on impressions, clicks, and engagement growth, and marketers are trained to identify and replicate whatever formats are currently performing best. Producing content that follows visible trends is often how value is demonstrated internally — and how roles, budgets, and compensation are justified.

In that environment, copying successful formats is not irrational. It is a response to how performance is evaluated.

The problem is that these incentives tend to reinforce sameness. When prompts and templates are reused at scale, they:

Encourage imitation over original thinking

Reward speed over clarity

Optimize for engagement metrics rather than insight

The result is a familiar feedback loop:

One format performs well

It gets copied widely

AI systems reproduce it efficiently

Readers grow fatigued

AI is blamed for the sameness

At the core of this loop is instruction, not intention. When a single prompt structure is reused thousands of times, it creates a shared stylistic baseline. Content begins to resemble itself not because ideas are converging, but because the instructions are.

Platform dynamics amplify this effect. Algorithms tend to reward familiarity:

Hooks that resemble previous high performers

Formatting that signals “this worked before”

Language optimized for skimming rather than depth

Over time, this encourages creators and teams to stick closely to proven formulas — not out of lack of creativity, but because predictability is rewarded.

What is increasingly outdated, however, is the assumption that maximum engagement is the primary path to discovery.

As AI-driven search and recommendation systems become more prevalent, visibility is no longer determined solely by who generates the loudest response. Increasingly, it is determined by whether content is well-written, clearly structured, and easy for AI systems to understand and surface.

In that context, originality, clarity, and thoughtful organization matter more than trend replication. Well-constructed articles that communicate ideas cleanly are often more discoverable — and more durable — than content optimized purely for short-term engagement spikes.

AI did not create the copy-paste incentive. It existed long before generative models entered the workflow.

AI Reflects Human Inputs, Not Human Intent

AI systems do not decide what is meaningful, timely, or relevant. They do not understand goals, values, or audience impact unless those considerations are made explicit in the prompts.

They respond to:

The specificity of the prompt

The originality of the source material

The constraints imposed by the user

In other words, AI operates on instructions, not intent. Humans often forget that AI is not present in the meetings where goals, context, and nuance are discussed. Just because AI is powerful does not mean it automatically understands what we are trying to accomplish.

When humans outsource thinking — or assume that AI can infer meaning on its own — instead of using AI to support thinking, the outcome is predictably the same.

A marketer, strategist, or founder may intend to:

Offer a fresh perspective

Challenge a common assumption

Clarify a complex issue for decision-makers

But if the instruction given to the AI is generic — “write a post about why AI matters” or “create thought leadership content for executives” — the system has no visibility into that intent. It can only respond to the literal task.

A familiar business example is a product or strategy announcement. Internally, teams understand the tradeoffs, customer pain points, and strategic implications. But when AI is asked simply to “announce a new feature” or “summarize benefits,” the output defaults to familiar language and surface-level framing.

This is why AI output often feels insightful when paired with strong direction — and flat or repetitive when used as a substitute for it. It also explains why certain prompts consistently perform better than others: they provide clear direction for the model rather than vague instructions.

Effective AI-assisted content creation depends on human decision-making upfront:

What is the actual point of this message?

Who needs to understand it, and why?

What context would change how it’s interpreted?

These questions give AI direction. They are what allow writing to feel fresh and meaningful instead of generic — and what turns AI from a text generator into a useful collaborator.

As AI becomes more embedded in search and discovery, the ability to frame intent clearly is becoming more valuable, not less. When intent is structured, AI becomes a powerful amplifier. When intent is left unstated, AI fills the gaps with default language it assumes is appropriate.

Why Editorial Judgment Still Matters

Editorial judgment is the layer that sits between information and publication. It determines what is emphasized, what is removed, and what is left unsaid.

This applies far beyond journalism. In business, editorial judgment shows up in everyday decisions teams make before anything is shared publicly. It influences:

Which product updates are highlighted versus quietly shipped

How customer problems are framed — as features, benefits, or outcomes

Whether a message educates, reassures, or persuades

When not communicating is more effective than publishing another announcement

A product team may have pages of release notes, but editorial judgment determines what customers actually need to know. A marketing team may have access to extensive performance data, but editorial judgment determines which insight is meaningful rather than merely measurable. A leadership team may have a clear internal strategy, but editorial judgment determines how much context an external audience requires — and how much detail would distract rather than inform.

It is human judgment and assessment, applied before content reaches an audience.

AI can draft quickly, but it does not evaluate:

Whether a point is redundant

Whether a framing is misleading

Whether a sentence adds value or merely fills space

When editorial judgment is skipped, AI-generated content tends to expose its own scaffolding: repeated phrases, familiar arcs, and predictable conclusions. This is not because AI lacks nuance. It is because nuance requires choice.

Strong AI-assisted writing still requires:

Clear framing

Source discernment

Intentional structure

Willingness to discard generic output

AI can accelerate drafting, summarization, and synthesis. It cannot replace the responsibility to decide:

What matters

What is redundant

What adds value for the reader

Those decisions are not technical. They are editorial.

The willingness to remove “good enough” language — even when it is fluent and technically correct — is what separates distinctive work from generic content. When editorial judgment is absent, AI doesn’t create the problem. It simply makes the problem visible faster.

As AI-generated content becomes more widespread across marketing, product, communications, and leadership workflows, this layer of human judgment becomes more valuable, not less. In AI-mediated search and discovery environments, clarity, structure, and intent are what allow content to be understood, surfaced, and trusted.

Editorial judgment is no longer just a publishing standard. It is a competitive advantage.

When Confidence Replaces Judgment

One of the more subtle challenges of AI-assisted writing is that it can feel like thinking is happening — even when it isn’t.

Copying a “successful” prompt, selecting from polished outputs, or lightly editing confident-sounding text all look like active decision-making. For many people, especially those under time pressure, this feels indistinguishable from original work. The result is a sense that the content is thoughtful simply because it sounds complete and authoritative.

But language that sounds confident is not the same as understanding.

AI systems are exceptionally good at producing writing that appears coherent, authoritative, and well-structured. When someone is less familiar with a topic, that confidence can be mistaken for insight. Generic explanations can feel “good enough” — or even impressive — when you don’t fully understand the subject you’re writing about, because there is no internal reference point for what stronger thinking would actually look like.

This is where judgment quietly drops out of the process.

In many cases, people are not intentionally skipping judgment. They believe they are exercising it. They reuse prompts that have worked for others. They rely on formats that perform well. They assume the model will infer what matters. What’s missing is not effort, but judgment.

Judgment shows up in questions like:

Do I actually understand this well enough to explain it to someone else?

What context would change how this is interpreted?

What should not be said because it would be misleading, incomplete, or overly simplified?

Without those checks, AI output can move from helpful to risky — especially when it is used to advise, persuade, or educate others. In those cases, confident-sounding but shallow content can shape decisions, influence opinions, or spread oversimplified guidance without the author realizing where the gaps are. Over time, this can lead to avoidable mistakes, misaligned strategies, wasted time, or initiatives and pilot programs that look promising on paper but fail to deliver in practice.

AI dramatically expands access to tools and capabilities that were previously out of reach. That access is valuable. But access does not remove the need for responsibility or limits.

Just because content can be generated does not mean it should be published — especially when the writer lacks enough familiarity with the topic to recognize where nuance, context, or restraint are required. Writing about what you understand makes it easier to see when AI output needs correction, clarification, or deeper framing — and when it’s being reduced to attention-seeking summaries rather than meaningful explanation.

Just because language sounds confident does not mean it reflects sound judgment.

AI models are designed to produce confident, authoritative-sounding language. It is the human’s role to supply judgment and critical thinking — to recognize when something sounds off, oversimplified, or incomplete. That responsibility does not disappear just because the tool is powerful.

Q&A: Why AI Writing Feels Repetitive

Q: Why does so much AI-generated content sound the same?

A: Because the same prompts, templates, and “best-performing” formats are reused at scale. When thousands of people ask AI to produce similar content with similar instructions, the output naturally converges.

Q: Is this a limitation of AI models?

A: No. Large language models are doing exactly what they are designed to do — respond accurately to the instructions they’re given. The limitation is usually in human input, not model capability.

Q: What role do prompts play in this sameness?

A: Prompts shape structure, tone, and emphasis. Recycled or generic prompts remove variation, which leads to predictable outputs even when the topic changes.

Q: Why does confident-sounding AI content still feel shallow?

A: Confidence is not the same as understanding. When writers lack deep familiarity with a subject, fluent AI output can appear insightful even when it lacks nuance or context.

Q: What does “editorial judgment” mean outside of journalism?

A: Editorial judgment is human decision-making applied before publication — deciding what matters, what’s redundant, and what adds value. It applies to marketing, product, leadership, and strategy, not just media.

Q: How should organizations use AI more effectively?

A: By treating AI as a collaborator, not a replacement for judgment — supplying clear intent, context, and constraints, and being willing to discard “good enough” output.

What This Means: Human Responsibility in the Age of AI Writing

The concern that AI-generated content sounds repetitive or the same is understandable. But it points to a deeper issue than the technology itself.

As AI becomes embedded in how information is created, summarized, and discovered, the differentiator is no longer access to AI tools. It is the quality of human direction applied to them. When prompts, templates, and incentives remain vague, narrowly defined, or copied from others, the output reflects those limits. When intent is clear and judgment is applied, AI becomes a force multiplier rather than a flattening one.

This matters for organizations of all sizes. Content now competes not only for human attention, but for interpretation by AI systems that summarize, recommend, and surface information. In that environment, material that is clearly framed, thoughtfully structured, and grounded in real understanding is more likely to be discovered, trusted, and reused than content optimized solely for short-term engagement metrics like reach and clicks — especially when teams are willing to resist copy-paste incentives.

AI does not eliminate the need for thinking. It raises the cost of skipping it.

Organizations that treat AI as a collaborator — not a replacement for human judgment — will produce work that feels distinct, credible, and useful. Those that rely on automation without clear intent or direction will blend into an increasingly crowded background where everything starts sounding the same.

AI reflects the quality of human direction. If the output feels the same, it may be worth examining the inputs — and the expectations — first.

This article is Part 1 of a two-part AiNews explainer.

In Part 2, we explore why AI doesn’t erase individuality — and how voice, intent, and interaction become more important as AI-generated content becomes more common.

Editor’s Note: This article was created by Alicia Shapiro, CMO of AiNews.com, with writing, image, and idea-generation support from ChatGPT, an AI assistant. However, the final perspective and editorial choices are solely Alicia Shapiro’s. Special thanks to ChatGPT for assistance with research and editorial support in crafting this article.